Category: DYES AND CHEMICALS

Country: Japan

By Joanna Kawecki

Contributing writer

1st November, 2025

Reading time: 6 min

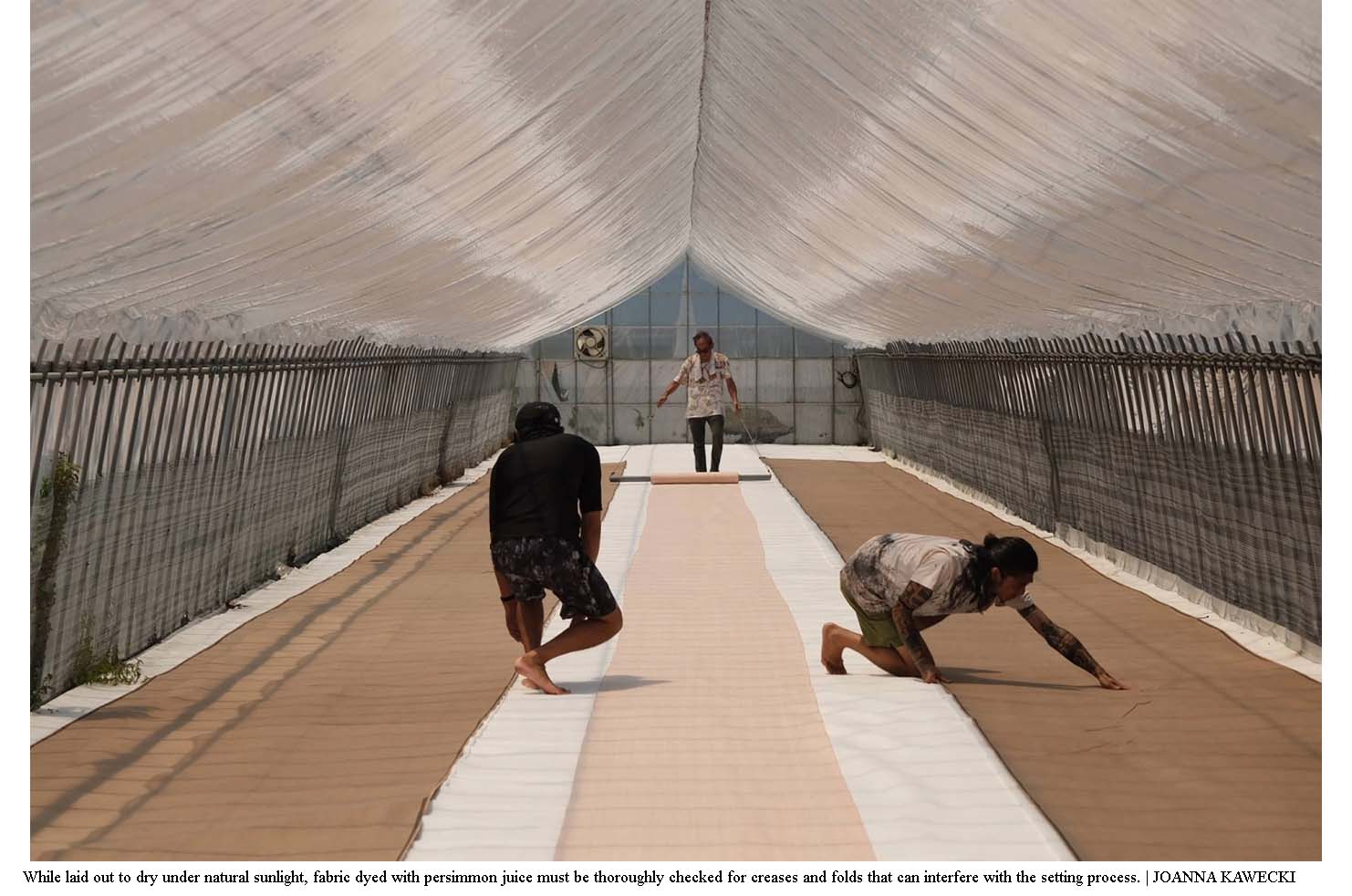

Higashiomi, Shiga Pref. – On a hot summer day in July, it’s nearly 45 degrees Celsius inside this greenhouse in Shiga Prefecture. Along with the humidity, though, there’s another type of moisture in the air: the deep burnt orange of kakishibu (persimmon juice) setting into the threads of 30-meter lengths of fabric laid out to dry.

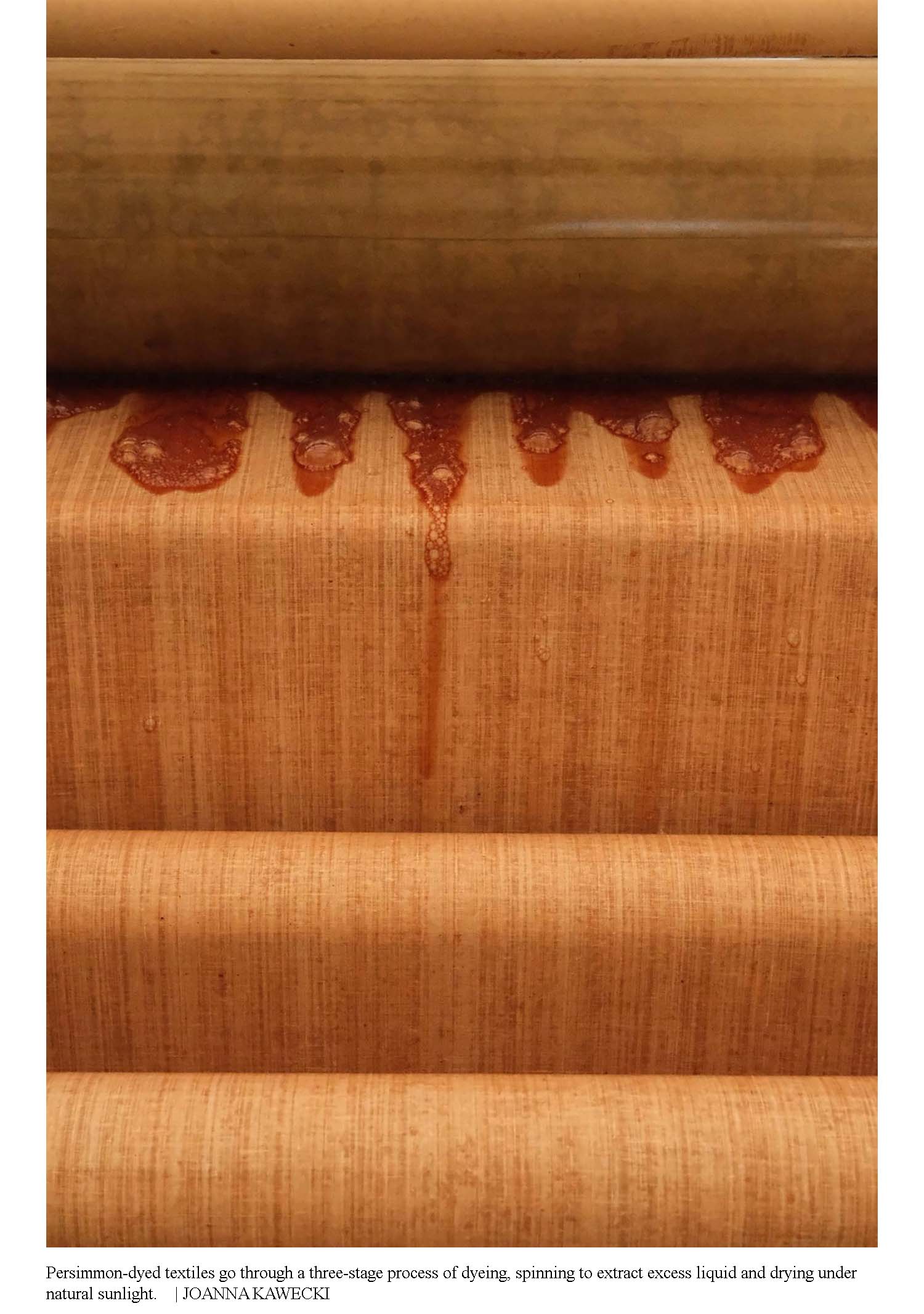

Through sun exposure and repeated immersion in containers of the natural dye, the textiles will gain a light amber tone before developing a darker gradient to be used for trousers, shirts and jackets.. This, second-generation textile worker Kiyoshi Omae tells me, is kakishibu-zome, a natural dyeing method from kaki (Japanese persimmons) used in Japan for more than a millennium.

“You don’t notice its function,” Omae says. “It is like an unseen barrier that creates a kind of protection and filter for the air.”

Persimmon tannin dye utilizes a fermented liquid derived from pressing and aging unripe green persimmon fruit for two to three years, a process overseen by a specialist known as a kakishibu-ya. Unlike aizome (natural indigo dye) that produces a deep blue color when the dye is exposed to air and subsequently oxidizes, persimmon tannin dye reacts to sunlight and results in hues of orange, amber and brown.

In ancient times, the dyeing technique was used on everything from timber to washi paper and natural textiles. The mold-resistant, insect-repelling and waterproof dye was also utilized by carpenters and timber craftsmen to coat wood. Fishermen and farmers used kakishibu-zome for clothing and tools such as fishing nets. Artisans of katazome, a stencil dyeing method for silk kimono, would use persimmon-dyed stencil paper for its strength and durability.

Even at 72 years of age, Omae is irrepressibly passionate about the natural dye. Through his company, Omae Co. Ltd., the Shiga native believes the centuries-old practice has enough contemporary function to keep the traditional craft alive.

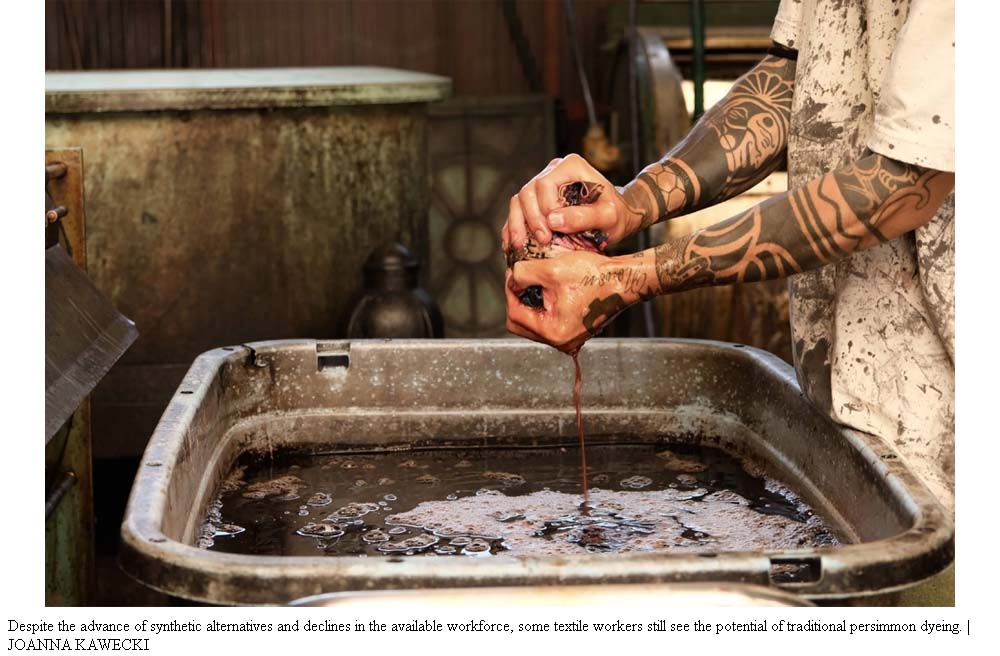

Persimmon tannin-dyed textiles are created through a three-stage process of dyeing, spinning and drying. Depending on the desired color and depth, the cycle can be repeated up to three times. Any excess liquid, extracted by a large, stainless steel spinning machine, can be reused over and over, and the textile is dried in large greenhouses, where abundant, natural light can activate the tannins while protecting it from wind, animals and insects.

“Ultimately, it is a completely sustainable method of production,” he adds. “I want to embrace natural resources in my production.”

Located in Higashiomi, Shiga Prefecture, Omae’s dyeing workshop sits in the only region in Japan that once produced three major textiles (cotton, silk and linen) thanks to its proximity to Lake Biwa, the country’s largest freshwater lake. The lake’s abundant water and high humidity offered ideal conditions for textile production. Since at least the 17th century, the village of Higashiomi has produced quality linens like ramie or hemp alongside silk in Nagahama on Lake Biwa’s northeastern shore, while cotton was produced in Takashima across the water to the west.

Working alongside Omae inside the greenhouse is his son, Akira Omae, 39, and Shinya Mizutani, 41. The pair investigate the fabric for creases or folds that might interfere with the drying process. While Akira grew up among his father’s fabrics, Mizutani previously worked for two decades in Tokyo’s fashion industry and started his own eponymous streetwear line in 2023 after joining Omae in 2021.

“When I first came here to (Omae), of course there was a base of great craftsmanship, but at the same time I felt something was missing and aimed to fill in the gap to adapt the product (to other industries such as streetwear),” he says. “I can’t do it alone, but with a team we can take (persimmon tannin dye) onto the world stage.”

Mizutani’s personal network in the fashion industry has led to a series of persimmon tannin-dyed carrier bags for storied Japanese bag brand Yoshida & Co. The collection also featured kure-zome, another traditional dyeing technique where iron is added to the persimmon tannin dye as a mordant. By adding the iron, it transforms the dye into a darker liquid resulting in tones of gray and black.

The industry is seeing a steep decline in popularity against cheaper, mass-produced synthetic alternatives, and the future of kakishibu dye is directly affected by Japan’s aging and declining population. In addition, the increased presence of Asiatic black bears within residential areas abutting undeveloped woodlands also adds an element of danger for farmers who cultivate persimmon fruit.

“Persimmon farming is typically grown in the mountainside where large machinery cannot access, so the fruits are often picked manually,” Omae says. “This type of work is now not as desirable.”

Omae sources its kakishibu dye from Kyoto Prefecture’s Iwamoto Kametaro, which currently produces half of all such dye in Japan.

Omae sources its kakishibu dye from Kyoto Prefecture’s Iwamoto Kametaro, which currently produces half of all such dye in Japan.

“Currently there are only three makers left that can create the liquid at industrial volumes,” Omae says.

While 45% of the persimmon juice goes to textile workers like Omae, 55% is used in food production. As the fruit is high in antioxidants and anti-inflammatory properties, it was historically used as folk medicine; today, the juice is a component in health supplements, soaps and aromatic sprays.

Ultimately the market will dictate the trends, notes Omae. However, he believes that the dye’s environmentally friendly approach to the textile production process is key for the craft’s future.

“This technique has been here for 1,000 years, so I want it to keep going and pass it onto the next generation.”

Courtesy: japantimes.co.jp

Copyrights © 2026 GLOBAL TEXTILE SOURCE. All rights reserved.